Rare and forgotten foods and their importance today

Today, our diet is characterized by great diversity and foods that were either very rare or completely unknown in Europe until a few centuries ago, such as potatoes, tomatoes, corn or tropical fruits such as bananas and pineapples, are now part of our diet as a matter of course.

While the first bananas only arrived in Germany from Madeira and the Canary Islands towards the end of the 19th century, dried and sweetened pineapples spread across Europe as early as the 16th century and were even grown in greenhouses here, but initially remained a delicacy reserved for the rich.

The situation was different with potatoes, tomatoes and corn. Initially eyed with suspicion and not widely grown, they were soon on everyone's lips.

The potato in particular stood out due to its excellent nutritional profile and good digestibility.

Rich in carbohydrates and other nutrients such as potassium and magnesium, it quickly became popular with the population in Europe after initial teething troubles and was soon appreciated as an easy-to-cultivate staple food.

While the above products have only been known and available in Germany for a comparatively short time, there are other foods that were introduced and distributed much longer ago and thus had a distinct history of use, but are now often forgotten, very rare or only enjoy regional fame or popularity.

We would like to introduce some of them here.

The medlar or Mespilus germanica - an almost unknown fruit:

Medlars on the tree

Let's start with the medlar, or Mespilus germanica in Latin, a shrub or tree that grows up to 6 meters high and forms a spreading crown on which numerous fruits are ready to be harvested in autumn. The fruits appear brown to orange, round and form a small crater at the top, from the edge of which small pointed sepals protrude upwards.

This fruit, which should not be confused with mistletoe, a parasitic plant that grows on trees, was introduced to Western Europe by the Romans and was a valued fruit for many centuries, partly because it is only slightly susceptible to pests and diseases and makes few demands on the location.

The medlar was cultivated by monks, particularly in monastery gardens. To become edible, they require either frost or prolonged storage. The consistency then becomes quite soft, almost mushy, and the taste takes some getting used to, as the fruit is only slightly sweet but astringent.

Nowadays, the medlar is unfortunately only rarely found in gardens, but sometimes in wild form by the wayside. Its use is correspondingly sparse.

In Saarland, medlars are used to distil the so-called Hundsärsch schnapps. The medlar is popularly known as Hundsärsch because its shape is said to be reminiscent of a dog's hindquarters.

The Japanese loquat has a much more pleasant taste but is only distantly related to the true medlar.

This is still cultivated today on some plantations in southern Europe and has a very aromatic and pleasant taste when fully ripe.

You can find a video about the Mespilus germanica below.

Another fruit that was introduced to Western Europe by the Romans is the sweet chestnut, also known as the chestnut tree.

The sweet chestnut - brown, round, tasty and now rare

Similar to the medlar, the sweet chestnut has little commercial value today, its use has become quite rare and it is probably only known to most people as a tasty snack at the Christmas market.

This used to be different in earlier centuries and still is today in some European countries in southern Europe.

Originally from the Caucasus, the sweet chestnut spread rapidly from the 9th century BC towards the Mediterranean region, where it was mainly used by the Greeks as a source of flour, bread and soups.

The Romans eventually settled the sweet chestnut throughout the Roman Empire and made it an important source of food.

The carbohydrate content of chestnuts in particular made them an interesting food and they became an important staple food throughout Europe between the 6th and 19th centuries. In Corsica, as you can see in the following video, it is still one of them today.

As with wine in other parts of Italy, it was the monastic orders that changed the history of the chestnut by reforesting mountain areas and planting new trees in the Middle Ages. Working for them were the castagnatores, peasants who were taught by the monks how to look after the forest and the chestnut trees, whose fruits were historically intended to feed the poor mountain population.

This is all too understandable, as cereals such as wheat and rye often grew sparsely on the barren mountain slopes and produced only low yields.

The sweet chestnut, on the other hand, copes well with poor soils and provided up to three times more calories than cereal crops grown on a comparable area.

As the trees flower relatively late, they were protected from frost and therefore always produced a reliable harvest, which, according to forestry inspector Friedrich Merz, saved the population from certain starvation in times of economic hardship. This was the case in the 1940s, for example, when potato blight struck the whole of Europe and caused a devastating famine, especially in Ireland.

In addition, chestnuts have a very long shelf life when dried and are therefore easy to store.

However, the chestnut not only provided food for humans, but is also attractive to bees during its flowering season, which produce a unique tasting chestnut honey thanks to the sweet chestnut nectar and honeydew.

Despite the many advantages offered by the sweet chestnut, it was gradually replaced by potato and cereal cultivation.

There were many reasons for this. On the one hand, the more effective use of fertilizers began in the 19th century and, on the other, mechanized soil cultivation.

For centuries, people had the problem that fertilizer was scarce in relation to the arable land used. So while today we tend to struggle with over-fertilization and the associated problems such as increased nitrate levels, the exact relationship between fertilizer and plant growth was not only unknown, but also caused problems for various reasons.

On the one hand, there was too little animal manure available overall, either because there were simply too few animals. For example, because animal husbandry was naturally a sign of prosperity, as they were expensive to buy and therefore reserved for the wealthier in larger quantities. Or because they were sometimes slaughtered before winter due to a lack of food, as otherwise they could not have been fed and were generally fed a meagre diet anyway.

On the other hand, many animals were left to fend for themselves on communal land and forests, the so-called commons, which meant that the droppings were either lost completely or only benefited the fields to a limited extent.

Chestnut tree in the fall

This initially changed in small steps.

From the 18th century onwards, the fields were no longer left to lie fallow for regeneration, but were planted with nitrogen-enriching plants such as legumes or clovers.

The next step was the use of liquid manure, i.e. nutrient-rich animal urine, which was first collected and then applied to the fields as fertilizer.

From the middle of the 19th century, chemically produced fertilizers came into fashion, which increased rapidly and made the cultivation of potatoes and cereals much more productive.

Another reason for the increased use of potatoes and cereals instead of chestnuts was the structural change brought about by modern agricultural equipment.

Mechanization in agriculture also began in the middle of the 19th century. Motor-driven machines were used for the first time, replacing the horse-drawn plow that had been common up to that point and enabling many times more work to be done than before. Today, the construction of greenhouse complexes also contributes to the production of large quantities of food.

As a result, the chestnut forests lost more and more of their economic importance until chestnuts became an increasingly rare foodstuff and were less and less on the menu. The chestnut forests were thus increasingly left to their own devices and became increasingly overgrown until the sweet chestnut, once known as a bread tree, fell into relative oblivion, with the exception of a few regions.

Nowadays, the sweet chestnut is experiencing a small renaissance as more and more people are interested in and opt for a varied regional and climate-friendly diet.

In the following video, you can find out how the chestnut forests are progressing and how they are defying climate change.

Incidentally, the sweet chestnut is not related to the horse chestnut, which looks similar, which is why its fruit should not be consumed.

Another food that was on the menu of the poor rural population for centuries and was eventually almost completely replaced by the potato and cereals was hemp. Today, this plant is also experiencing a small renaissance. There are many reasons for this.

Hemp - from staple food to almost forgotten superfood

Originally from north-western China, the plant has been cultivated for around 12,000 years and has naturally found its way to Europe and other parts of the world over the millennia, where it can be found growing wild almost everywhere today.

In the past millennia, the hemp plant was not only known for its nutritional properties, but also had numerous other uses.

Hemp is a very hardy plant with a robust and above all long plant fiber and was therefore used wherever resilient and durable materials were needed. On the one hand, hemp fiber was used in shipbuilding for the production of ropes and sailcloth. In 17th century Europe in particular, hemp was an indispensable raw material, as overseas trade from the Netherlands began to flourish in this century.

This was also known as the "Golden Age" and brought the Netherlands an enormous economic boom and prosperity due to the invention of the sawmill, the associated much faster ship construction and the resulting superiority as a trading power, as can be seen in the following 4-part Arte documentary.

This could also be stopped by the parallel wars, such as the 30 Years' War or the Dutch-Spanish War.

On the other hand, hemp fiber was widely used in the textile industry alongside wool and even took a dominant position here. Cotton, which was smoother and easier to process, was still in short supply and only accessible to the wealthier population due to its rarity.

Hemp, on the other hand, was available everywhere and was therefore widely used for the production of durable clothing.

However, another industry also benefited from this versatile plant. The paper industry.

Paper spread from China to Europe from the 11th century onwards. A mixture of hemp fibers and flax was mainly used here.

The paper mills that emerged from the 13th century onwards simplified the paper production process, so that paper soon gained the upper hand over the parchment that had been used until then.

At the latest with the invention of the modern printing press with movable type by Johannes Gutenberg, paper became widespread in Europe.

Both the famous Gutenberg Bible and the US Declaration of Independence were printed or written on hemp paper.

However, hemp was not only valued for its fibers, but was also widely used in nutrition, especially by the poor rural population.

This was due to the excellent nutritional properties of hemp seeds. Hemp seeds have a high oil and protein content.

The 30-35% fats contained in unhulled hemp seeds consist almost exclusively of polyunsaturated fatty acids, especially omega-6 and omega-3.

At 25-30%, the protein content is in no way inferior.

Hemp was therefore an important and rich foodstuff in times of scarcity.

There is evidence of the use of hemp as a foodstuff, especially from the late Middle Ages up to the 18th century. There are mentions of hemp puree, hemp porridge, hemp curd and hemp dumplings, which certainly indicate its extensive use.

Hemp seeds were probably also widely used as a fasting food.

You can find a nice essay on the historical use of hemp as a foodstuff at the following link.

However, it was only a matter of time before hemp was replaced.

As with chestnuts, the decline of hemp as a foodstuff was sealed by the advent of better fertilization methods and the progressive mechanization of agriculture.

In the paper industry, there were numerous attempts to replace hemp fiber with other materials. However, it was not until the middle of the 19th century, with the invention of the so-called wood grinder, that they really became successful.

This machine made it possible to mechanize the defibration of wood, a process that resulted in a pulp that was a raw material for the industrial and cost-effective production of paper.

Fiber hemp after the harvest

As wood itself was available in large and cheap quantities, hemp became increasingly rare as a raw material for paper and was soon replaced.

Hemp and its equal partner, wool, also soon became obsolete as raw materials for the textile industry.

As already described in the guidebook article "The Aspermill - through the ages", the cotton industry in the USA experienced an enormous boom from the end of the 18th century due to the exploitation of African slave labourers and the emerging mechanization.

On the one hand, the massive exploitation of slaves meant that cotton could be grown and harvested on a large and cheap scale, especially in the southern states of the USA.

Secondly, the invention of the cotton gin by Ely Whitney in 1793 made it possible to process cotton on a large scale by machine, which previously could only be sorted by hand in small quantities.

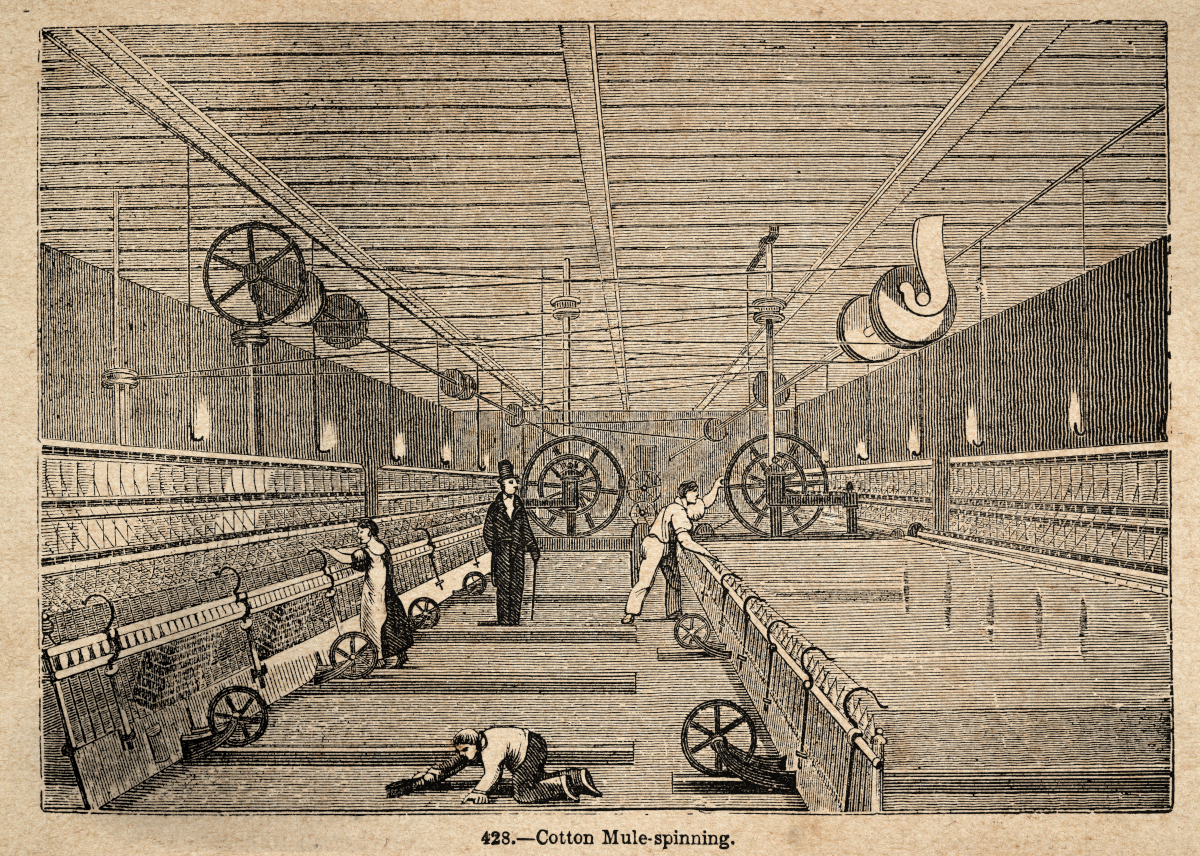

Further inventions such as the 'spinning jenny' or the water-powered "waterframe" paved the way for further inventions in this area and, of course, the way for machine processing and thus the mass production of cotton fabrics. The following picture shows a so-called'spinning mule'. This was a combination of 'Spinning Jenny' and 'Waterframe' and could carry up to 1000 spindles for yarn production at the same time. It is easy to imagine that such a machine saved an enormous amount of manpower and was therefore able to produce cotton yarn cost-effectively in a much shorter time.

Hemp was almost completely obsolete.

Nowadays, people are once again focusing on the positive properties of hemp, which has a number of advantages over its competitors, particularly in terms of sustainability. Since industrial hemp was re-approved in the EU in 1996, both the fiber and the seeds used for food have regained importance.

Hemp is relatively undemanding to grow and, unlike cotton, requires very little water. It is also quite resistant to pests and therefore requires little or no crop protection. As it grows quite well even on poor soils, can cope with small amounts of fertilizer and, depending on the variety, can be cultivated in Europe without any problems, hemp is ideally suited to today's world, which is determined by the idea of sustainability.

As already described, hemp seeds provide high-quality polyunsaturated fatty acids and are rich in protein. The protein in hemp seeds contains all 8 essential amino acids, i.e. all the protein building blocks that the human body cannot produce itself.

This is why athletes on a vegan diet in particular like to use hemp protein powder.

Hemp seeds also contain iron, magnesium, zinc, vitamin B1 and vitamin E. This makes them a real regional and environmentally friendly superfood.

Hemp still plays a niche role in the clothing industry today, which is due to the fact that hemp fibers are quite uncomfortable to wear in contrast to cotton and machines or chemical processes that can be used to process the hemp fiber into a fine yarn have not yet established themselves in Europe.

As a result, hemp is currently mainly used in the construction and automotive industries.

In the automotive industry, hemp fiber is used for door panels due to its stability.

In the construction industry, hemp fiber is once again coming into focus due to its excellent insulating properties.

In combination with lime or clay, this results in excellent building materials that are highly moisture-regulating and insulate against heat and cold, thus ensuring a pleasant indoor climate all year round.

You can find out more about hemp as an insulating material below.

Another advantage is its environmental compatibility. During the construction process, material made from hemp is CO2-neutral. If the components built with hemp fibers are ever demolished, the building material can simply be returned to the natural cycle.

Ornamental quince - little known as a foodstuff - but still appreciated by connoisseurs

We now turn to a relative of the medlar described above, the ornamental or false quince (Chaenomeles japonica). In contrast to the quince growing on the tree (Cydonia oblonga), most people are probably no longer familiar with it as a food.

This is a real shame, because the ornamental quince has an incomparable aroma that even surpasses that of its big sister.

Like the medlar, the ornamental quince is a pome fruit plant. The shrubs originally come from Japan and China, from where they found their way to Europe at the end of the 18th century.

As a rule, the shrubs grow between 1-1.5 m tall, but can also grow up to 3 m tall depending on the variety.

In spring, they are early bloomers and their orange to red, sometimes also white, flowers provide wild bees and bumblebees with nectar and, above all, plenty of pollen.

Their bright yellow fruits, around 5-6 cm in size, ripen in late summer and exude a pleasant fruity, aromatic scent.

The ornamental quince is often found along roadsides, in gardens or in attractively landscaped parks.

The ornamental quince is not only beautiful to look at but, like its big sister the tree quince, also has a wonderfully aromatic smell and taste.

It is not edible raw and would be too hard for that and the seeds inside are slightly poisonous.

When pitted and cooked, with sugar and perhaps a few spices, it develops a strong aroma that even surpasses that of the tree quince. However, as it is also much more acidic, it also requires relatively more sugar than the latter.

You can find out how to make a delicious jelly from ornamental quinces in the following video.

You can find some delicious recipes in our blog and advice section. Please note that these are written for large quinces and therefore more sugar may need to be added depending on the taste.

Of course, ornamental quinces are also suitable for fermentation.

The use of the fruit began in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century in the Ukraine and continued in mid-century in Latvia, where the aim was to breed the Chaenomeles japonica, which originated in Japan, into a variety that was both high-yielding and thornless. The result of these efforts was the "Cido" variety, also known as the Nordic lemon.

Larger plantations of mock quinces were established in Latvia, Poland and Lithuania in the 1970s and 1980s.

After the end of the Soviet Union, however, the cultivation of the fruit came to a standstill.

However, as people have become increasingly aware of healthy and conscious eating in recent years, the ornamental quince has also experienced a small revival. In the Baltic states, and especially in Latvia, there are now various plantations where the Cido quince can be found.

There are numerous ways of processing the Cido. Dried as an addition to tea, as jelly, compote or candied dried fruit with or without chocolate. Cido always makes a good shape.

You can also find various items with the tasty ornamental quince in our store.

However, we don't just want to dwell on native plants, but also turn our attention to somewhat more exotic species and we want to start with vanilla.

Vanilla - on everyone's lips and yet rarer than you might think

You might be thinking, vanilla? It's neither rare nor unknown. But real vanilla is rarer than you might think, mainly due to its laborious cultivation method.

The history of vanilla begins in Central America. Vanilla was a highly prized spice, especially among the Aztecs in Mexico, who themselves learned about it from the Totonaks, the inhabitants of the Gulf coast of Mexico, when they subjugated them in the middle of the 15th century. After their subjugation, the Totonaks had to pay part of their tribute in the form of vanilla pods.

Drying vanilla pods in the sun

Since this time, vanilla or tlixochitl (Aztec for black flower) has been consumed by the Aztecs in a drink called "xocolatl". The inclined reader will no doubt be able to guess that this was cocoa.

The bitter cocoa drink gained significantly more aroma and spice with the addition of vanilla, as vanilla is quite spicy in higher doses.

It should be mentioned that this original form of cocoa is not the same drink as we know it today. Rather, the cocoa beans were crushed and infused with water and possibly with corn flour, which gave the whole drink a certain creaminess or viscosity and then spiced, for example with vanilla or chili. The drink was sometimes flavored with salt and a little honey.

However, both cocoa and vanilla were by no means everyday foods for the whole population, but were reserved for the higher-ranking nobility, warriors and rulers.

Europeans first came into contact with vanilla when the Spanish invaded and subjugated the Aztec Empire between 1519-1521.

As vanilla grew exclusively in this part of the world at this time and the Spanish now had a trade monopoly on it, vanilla remained a rare rarity that was also reserved for the nobility, rich and rulers in Europe.

Initially, it was only used here as an ingredient in cocoa-based drinks, following the example of the Aztecs.

However, this changed at the beginning of the 17th century when Queen Elizabeth's apothecary Hugh Morgan developed vanilla-flavored sweets, which were highly prized by the Queen.

Vanilla was made even more famous by Thomas Jefferson, who learned to appreciate it as an ingredient in ice cream during his time as American ambassador in Paris between 1784 and 1789.

The recipe he knew probably came from his French butler Adrien Petit, who also held the title of maître d'hôtel and was therefore responsible for Jefferson's entire household organization.

After his time in Paris, Jefferson brought his love of ice cream and the corresponding recipe back to the USA, where it can still be found in the Congressional Library today.

This helped to increase the popularity of vanilla in the USA and demand skyrocketed.

This hype naturally became a problem, as Spain still had a trade monopoly on vanilla, as it grew exclusively in Mexico and all attempts to get it to fruit outside its natural habitat failed.

In 1836, the Belgian botanist Charles Morren believed he had discovered the reason for this. In order to bear fruit, vanilla flowers must be fertilized by specialized insects that do not exist outside Mexico. Morren believed that this fertilization was carried out by stingless Melipona bees and, more rarely, by hummingbirds.

However,more recent studies have not confirmed this, as the bee species is probably too small for this task. Current research assumes that pollination is carried out by larger bee species such as the wood bee (Xylocopa) or the Euglossine bee (Euglossini).

This means that only hand pollination was possible for the fertilization of the vanilla flower.

When the slave Edmond Albius finally discovered a simple method of fertilizing vanilla by hand in 1841 on La Reunion, which was under French colonial rule at the time and was then called Île Bourbon - hence the name Bourbon vanilla - the supremacy of the Spanish was broken within a short time.

In this method, which is still used today, the sticky pollen mass of the vanilla flower is picked up with a small stick and then pressed onto the female stigma.

A video illustrating the method can be found below.

Using this technique, the French quickly began to establish vanilla plantations on Reunion, Mauritius, Madagascar and the Comoros.

As vanilla species are climbing plants that belong to the orchid family and originally come from the rainforest, they need both a tropical climate and a system of climbing and support aids in order to thrive, as you can clearly see in the following picture.

Vanilla plantation with shade

Even today, most of the vanilla traded worldwide comes from Madagascar. However, while the island still had a market share of 80% until the mid-1980s, this fell to around 40% by the early 1990s.

As a result, Madagascar sells around 3,200 tons of high-quality bourbon vanilla, of the total amount of vanilla harvested worldwide of just 8,000 tons (as of 2017). This makes it one of the rarest foods in the world.

The main competitor is now Indonesia, which accounts for around 30%, although its vanilla is of inferior quality.

The other growing regions are spread across China, Mexico, Papua New Guinea, Turkey, Uganda and Tonga.

But it is not only the growing conditions that are difficult and require specialist knowledge to ensure successful cultivation. Post-harvest processing is also complex.

As a rule, the vanilla bean is harvested unripe and must then undergo heat treatment. This is usually done with water heated to around 65 degrees, in which the beans are immersed for a few minutes.

This ensures that the cell activity comes to a standstill, but the enzymatic activity is retained.

This is followed by "sweating", whereby excess moisture is removed, but enough remains to maintain the enzymatic activity.

This is the most important step, as the glucosides are broken down into vanillin, which gives the vanilla its typical aroma.

The pods are then dried in the sun to a residual moisture content of 20-30% and then stored for several weeks to months to further intensify the aroma.

Based on the difficult cultivation and processing process, you can imagine how labor-intensive it is to get from the cultivation of the vanilla orchid to the finished vanilla pod. This naturally ensures that vanilla pods fetch a high selling price, which in turn arouses covetousness and attracts vanilla thieves in Madagascar. This has now become a problem, as the following report shows.

However, this also attracts food fraudsters who try to deceive retailers and consumers with cheap imitations, e.g. synthetic vanillin, and make a profit at their expense, as investigations from France showed in 2019.

Even today, vanilla is still one of the rarest and second most expensive spices in the world. It is only challenged for first place by an even rarer spice, saffron. But we will report on this in the second part.

.jpg)

.jpg)